Now Reading: The Unexpected Cuisine of Lake Prespa: North Macedonia’s Other Lakeside Treasure

-

01

The Unexpected Cuisine of Lake Prespa: North Macedonia’s Other Lakeside Treasure

The Unexpected Cuisine of Lake Prespa: North Macedonia’s Other Lakeside Treasure

While Ohrid draws the crowds, Lake Prespa's tranquil shores host a unique culinary tradition where Armenian influences meet Macedonian ingredients, creating dishes you won't find anywhere else in the Balkans.

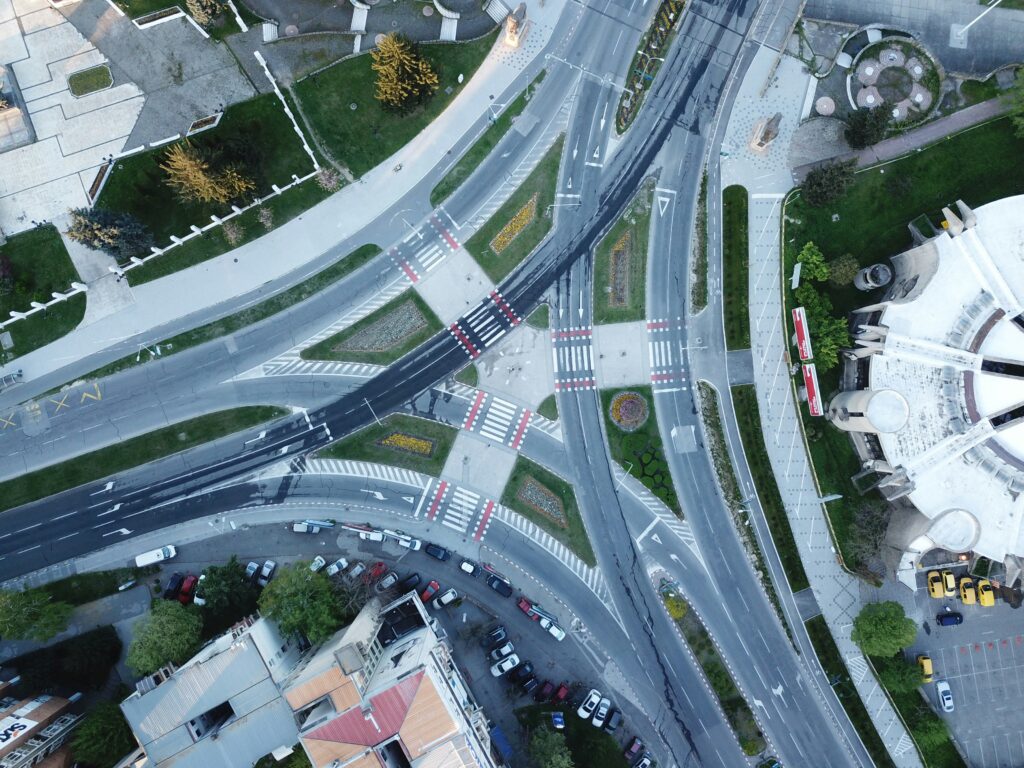

Nestled between mountain ranges along North Macedonia’s southwestern border with Greece and Albania, Lake Prespa sits like a forgotten sibling to the more famous Lake Ohrid. Yet those who venture to this serene expanse of blue discover not just breathtaking landscapes, but one of the Balkans’ most fascinating and little-known culinary traditions.

“Prespa has always been at a crossroads,” explains Elena Nikolovska, a local food historian whose grandparents settled in the region. “Armenian refugees arrived here in the 1920s, bringing cooking techniques that merged with local Macedonian ingredients and traditions. The result is unlike anything else in the country.”

This unique fusion is immediately evident at Brajcino House, a family-run restaurant in the lakeside village of the same name. Here, thin dough pastries known as kata are filled not with the spinach or cheese typical elsewhere in Macedonia, but with foraged wild herbs and lake fish preserved through a fascinating fermentation process similar to that used in Armenian cuisine.

“My grandmother taught me that nothing should be wasted,” says owner Gordana Angelovska as she serves plates of nasnifi – tender pike perch enhanced with wild thyme and preserved lemon, a dish that showcases the Armenian preservation techniques that proved vital in this once-isolated region.

The Armenian influence extends to spicing as well. While Macedonian cuisine typically employs simple seasonings, Prespa dishes feature aromatic spice blends incorporating sumac, dried mint, and zaatar. At Lakeview Restaurant in Pretor village, chef Dimitar Ristovski creates a remarkable trout dish crusted with these spices, then slow-roasted over apple wood from the region’s abundant orchards.

What makes Prespa’s cuisine particularly special is its seasonal specificity. “We have dishes that appear for just two or three weeks each year, when certain ingredients peak,” explains Ristovski. Case in point: the jufka so gabi – handmade pasta tossed with morel mushrooms that local families still forage in the beech forests climbing the slopes above the lake during the brief spring season.

Even fruits and vegetables develop distinctive characteristics in Prespa’s microclimate. The region’s famous apples benefit from the reflective qualities of the lake combined with sharp temperature drops at night, resulting in exceptionally crisp, sweet fruit that appears in everything from rakija to desserts. At the annual Apple Festival each October, visitors can sample over fifty varieties, many preserved through ancient techniques specific to the area.

For those accustomed to the hearty meat-forward dishes common throughout the Balkans, Prespa’s plant-based offerings come as a delightful surprise. “The Armenian influence brought a sophistication to vegetable preparation,” notes Nikolovska. This is evident in dishes like the patlixhani polneti – eggplants stuffed with walnut paste, pomegranate molasses, and herbs, then slow-roasted until silky.

Wine culture here differs from other Macedonian regions as well. Rather than the big, bold reds from Tikveš, Prespa specializes in aromatic white wines made from grape varieties uniquely suited to the lakeside terroir. The Macedonian-Albanian border actually cuts through vineyards in some places, with families traditionally working land on both sides. Skovin Winery now produces a Lake Line white specifically from these cross-border grapes, symbolizing the region’s borderless cultural heritage.

To truly experience Prespa’s culinary depth, visitors should venture beyond restaurants to the region’s small producers. The women’s cooperative in Ljubojno village produces perhaps the most extraordinary ajvar (red pepper spread) in Macedonia, incorporating Armenia-influenced techniques of slow charring and stone grinding. Their small shop also offers preserves like wild fig jam with mountain herbal infusions not found elsewhere.

Despite its uniqueness, Prespa’s food culture remains refreshingly unpretentious. Meals typically conclude with Turkish coffee prepared in copper džezva pots, alongside a small glass of fruit rakija and perhaps a paluška – a walnut-stuffed shortbread that again reveals its Armenian heritage through subtle spicing of cardamom and clove.

“We don’t need fancy presentation,” smiles Angelovska as she serves a final course of preserved wild pears in mountain honey. “When ingredients are treated with respect and recipes carry centuries of wisdom, the food speaks for itself.”

For culinary adventurers willing to venture beyond North Macedonia’s more established destinations, Lake Prespa offers not just magnificent natural beauty, but a living museum of cross-cultural cuisine that continues to evolve while honoring its unique heritage.