Now Reading: The Rakija Renaissance: How North Macedonia’s National Spirit is Getting a Craft Upgrade

-

01

The Rakija Renaissance: How North Macedonia’s National Spirit is Getting a Craft Upgrade

The Rakija Renaissance: How North Macedonia’s National Spirit is Getting a Craft Upgrade

Once considered merely a potent traditional spirit, rakija is enjoying a sophisticated revival as artisanal producers across North Macedonia reimagine this fiery fruit brandy for a new generation.

If you’ve spent any time in North Macedonia, you’ve likely been offered a small glass of clear or amber liquid, served alongside a knowing smile and perhaps a warning: “Slow down, it’s stronger than you think.” Rakija, the fruit brandy that serves as both national drink and cultural institution, has warmed Macedonian winters and celebrated harvests for centuries.

Traditionally home-distilled and ranging from 40% to eye-watering 60% alcohol, rakija has long been the domain of village grandfathers with copper stills and closely-guarded family recipes. But across North Macedonia, a new generation is reimagining this heritage spirit, bringing craft sensibilities and modern techniques to create premium versions that might surprise even the most traditional rakija connoisseur.

“We’re not trying to replace our grandfathers’ rakija,” says Nikola Petkov of Planinska Distillery in Kruševo, “We’re building on their wisdom and introducing some contemporary approaches.” Petkov’s limited-edition quince rakija recently won gold at the International Spirits Challenge in London, signalling that Macedonia’s national drink is ready for the global stage.

What distinguishes this new wave of craft rakija is attention to detail. At Vardar Valley Spirits in Negotino, wild pears are handpicked from specific mountain groves, fermented in temperature-controlled environments, and distilled in small batches using copper pot stills manufactured by the same family since 1927. The result is a remarkably complex spirit with notes of vanilla, cinnamon, and fresh pear that lingers elegantly rather than punching you in the palate.

Packaging has evolved too. Gone are the recycled plastic water bottles often used for homemade versions. Craft producers like Ohrid Spirit house their premium rakijas in sleek glass bottles with minimalist labels that wouldn’t look out of place on a craft gin shelf in London or New York. “The product inside remains authentic to our traditions,” explains founder Marija Stojanovic, “but the presentation helps introduce rakija to those who might otherwise never try it.”

Even the drinking experience is being reimagined. At Skopje’s fashionable Rakija Bar, flights of different varieties arrive with tasting notes and food pairings – a far cry from the traditional gulping alongside meze. “We serve it in grappa glasses rather than shot glasses,” says owner Stefan Dimovski. “We want people to appreciate the aromatics and complexity.”

The varieties extend beyond the classic plum, grape, and quince. Innovative distillers are experimenting with everything from wild fig to sour cherry, and even barrel-aging in Macedonian oak. Zito Distillery in Bitola has created a remarkable apricot rakija finished in barrels previously used for local red wine, creating a fruit-forward spirit with subtle tannic structure.

This craft approach is attracting international attention. Small-batch Macedonian rakijas now appear on the spirits lists of high-end restaurants in Berlin, Amsterdam, and London. “We’ve gone from ‘what’s rakija?’ to sommeliers actively seeking out our limited releases,” says Petkov proudly.

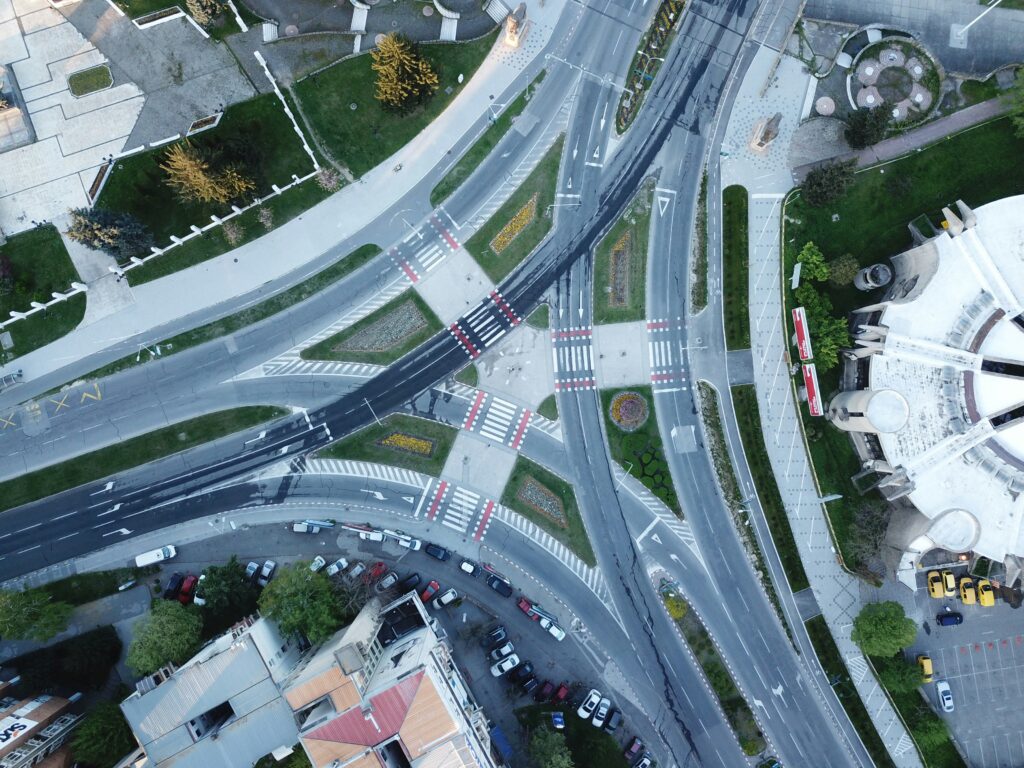

For visitors to North Macedonia, this rakija renaissance means unprecedented opportunities to experience the national spirit in new contexts. Distillery tours have emerged as a popular activity, with many offering tasting rooms overlooking the very orchards that supply their fruit. The annual Rakija Festival in Skopje each October has evolved from a folksy gathering to a sophisticated showcase of the country’s best distillers, complete with masterclasses and food pairings.

Despite the modern approaches, tradition remains at the heart of even the most progressive rakija producers. Many still time their distillation by the lunar calendar, insist on using wood fires beneath their stills, or maintain the custom of sharing the first distilled drops with neighbours as thanks for a successful harvest.

“At the end of the day, rakija isn’t just a drink for Macedonians—it’s part of our identity,” reflects Dimovski. “The craft movement is simply helping more people discover what we’ve always known: that a good rakija is something truly special.”