Now Reading: The Colourful Chronicles: North Macedonia’s Street Art Renaissance

-

01

The Colourful Chronicles: North Macedonia’s Street Art Renaissance

The Colourful Chronicles: North Macedonia’s Street Art Renaissance

Beyond ancient church frescoes, North Macedonia is experiencing an explosion of contemporary street art that's transforming urban spaces and telling new stories about national identity, with Skopje emerging as one of the Balkans' most exciting open-air galleries.

On a formerly nondescript concrete wall in Skopje’s Aerodrom district, a striking four-story mural depicts a young woman in traditional Macedonian dress, her face simultaneously reflecting centuries of cultural heritage and contemporary determination. This powerful piece by artist collective Color Revolution represents more than mere decoration – it’s part of a nationwide street art movement reclaiming public spaces and exploring national identity through a distinctly modern lens.

“For decades, our visual culture was dominated by either ancient religious art or socialist monuments,” explains Jana Jakimovska, co-founder of Urban Art Skopje, an organisation documenting and promoting street art across the country. “Street art gives us a platform to explore what being Macedonian means today, outside of institutional frameworks.”

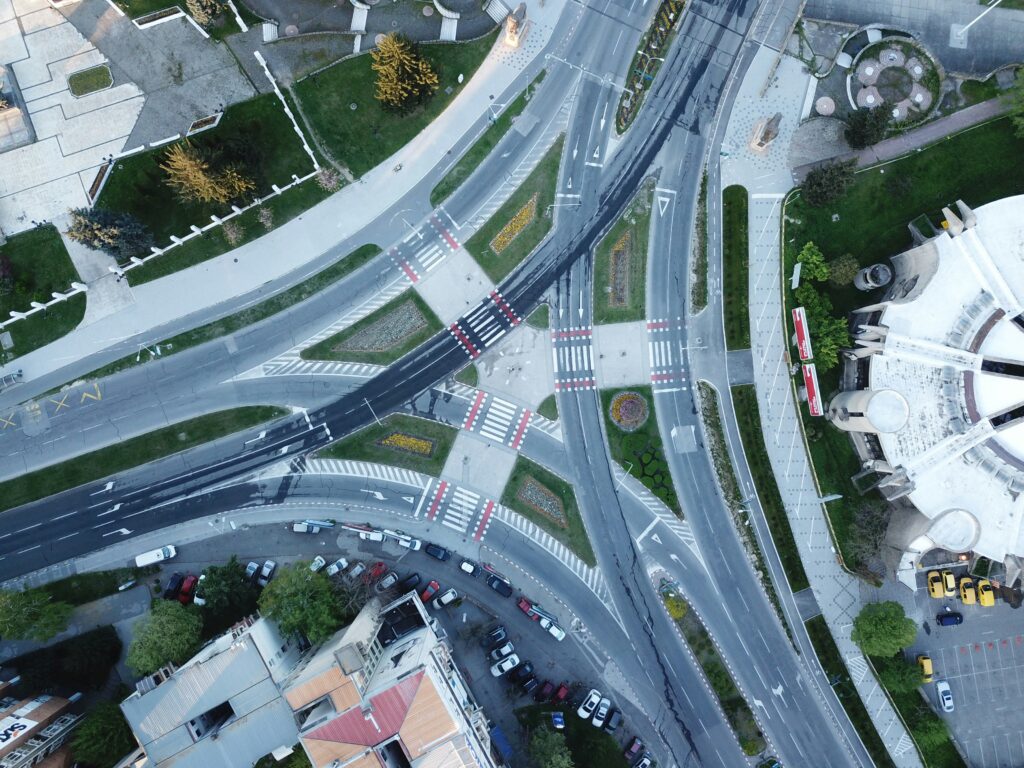

This exploration has transformed Skopje in particular. Once characterised by its controversial government-funded neoclassical buildings and monuments, the capital now boasts over 150 significant murals, with new works appearing monthly. From politically charged pieces addressing environmental concerns in the Novomaalo neighbourhood to celebrations of cultural diversity in the Old Bazaar, these works collectively represent an alternative vision of North Macedonian identity – one created from the ground up rather than imposed from above.

“We’re having conversations through these walls,” says prominent street artist Stefan Jakimovski (no relation to Jana), who works under the name STEFI. His recent mural near the city’s central park incorporates symbols from Macedonia’s various ethnic communities – Albanian, Turkish, Roma, and Macedonian – intertwined in a single harmonious design. “Art can build bridges where politics has built walls,” he notes.

What makes North Macedonia’s street art scene particularly exciting is its diversity of styles and influences. In Bitola, artist Natasha Dimitrievska creates hyperrealistic portraits of local cultural figures on building façades, while in Ohrid, the collective LakeWaves produces geometric abstractions inspired by traditional textiles and lake reflections. In Tetovo, calligraffiti artist VANE blends Arabic-influenced calligraphy with graffiti techniques to create works that honour the region’s Islamic heritage while feeling thoroughly contemporary.

This creative flourishing has been facilitated by increasing institutional support. The Skopje Street Art Festival, launched five years ago as a grassroots event, now receives municipal funding and attracts artists from across Europe and beyond. “Initially, authorities saw street art as vandalism,” remembers festival organiser Bojan Petrovski. “Now they recognise its cultural and tourism value.”

Indeed, street art tours have become increasingly popular among visitors. The free “Skopje Streets” smartphone app, available in English, maps significant works across the capital with artist information and cultural context. For deeper engagement, organisations like Exploring Macedonia offer guided street art walks led by local artists who provide insider perspectives on the creative process and social significance of various works.

“Visitors are surprised by the quality and quantity of our street art,” notes tour guide and art historian Mila Gavrilovska. “They often expect Skopje to be all about ancient history and those controversial government statues. The street art shows them the city’s creative, progressive side.”

The movement extends beyond major cities. In the wine region of Kavadarci, a remarkable project has transformed the entire village of Vataša into an open-air gallery, with over 30 murals depicting local wine-making traditions alongside contemporary themes. Created through collaborations between international artists and local residents, these works have reinvigorated village life and drawn visitors to an area previously overlooked by tourists.

Unlike street art in some Western European cities, which can contribute to gentrification controversies, North Macedonia’s scene remains deeply connected to local communities. “Before creating a mural, I spend time in the neighbourhood, talking with residents about what they’d like to see represented,” explains artist Martina Gelevska. Her community-based approach has resulted in works like “Remembering Together” in Skopje’s Čair district, which incorporates family photographs contributed by area residents into a collective portrait of neighbourhood history.

Environmental themes feature prominently as well. In Ohrid, a series of lakeside murals by the collective EcoArt draws attention to lake pollution through stunning visual metaphors. One particularly effective piece shows native Ohrid trout swimming through crystal waters that progressively transform into plastic waste – a beautiful yet disturbing reminder of environmental threats to the UNESCO-protected lake.

For foreign visitors, these artworks offer insight into aspects of Macedonian society rarely covered in guidebooks. “The murals tell stories about local concerns, aspirations, and values,” observes Gavrilovska. “They’re contemporary cultural artifacts that help people understand our country beyond historical sites and folklore.”

As North Macedonia continues defining its place in Europe and the world, its walls have become canvases for collective reflection on both past and future. “In a young country still forming its identity, these public artworks are visual contributions to an ongoing national conversation,” says Jakimovska. “They don’t provide definitive answers about who we are, but they ask important questions in visually spectacular ways.”